|

Introduction

'Dragon Search' is a national monitoring program which

encourages members of the community to provide information

about sightings of the unique southern Australian fish

- the seadragon. The information has been used to greatly

increase our understanding of the distribution, habitat

requirements and research and management priorities

for these little-known species. Anyone who visits the

beach in Australia has been able to get involved.

Although Dragon Search is no longer funded, many aspects

of this program have been incorporated into the South

Australian Reef Watch Feral

or In Peril program. In particular, reports

of sea dragon sightings can still be made. The data

will be stored in the Reef Watch database. In the future,

the data can be extracted separately for each state

to produce periodic Dragon

Search reports.

Other information that has been retained from the original

Dragon Search website includes the Code

of Conduct, archive of newsletters

and media releases, and the photo

library and video

footage.

Dragon Search

has been supported throughout Australia by the following

organisations

Further information can be found

under the headings below:

Syngnathids

Weedy

(Common) Seadragons

Leafy

Seadragons

Seaweed

Swayers

Male

Mothers, Wrinkly Tails and Egg Cups

'Take

Two Seahorses and Go To Bed...?'

Why

Survey for Seadragons?

You

Could be a Pioneering Scientist!

How

To Get Involved!

What

Are We Doing?

What

Are the Principal Aims of Dragon Search?

That

Face Looks Familiar

The

Database

I

Don't Dive or Snorkel, But Want To Help...

References

Syngnathids

Seadragons are found only in southern

Australian waters. Along with seahorses, pipehorses

and pipefish these spectacular fish belong to the Family

Syngnathidae. Syngnathids are long, slender fish with

bony plates surrounding their bodies. The Latin name

'syngnathid' refers to their jaws, which are united

into a 'tube-snouted' mouth.

The two species of seadragons, the Leafy

Seadragon (Phycodurus eques) and the 'Common'

or Weedy Seadragon (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus),

both have many leaf-like appendages on their heads and

bodies. The resemblance of seadragons to seahorses is

superficial as the two seadragon species are more closely

related to the pipehorses (Gomon et al. 1994).

Leafy Seadragon (Phycodurus eques)

Weedy Seadragon (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus)

Graphic by Sue Stranger (Untamed

Art)

Graphic by Sue Stranger (Untamed Art)

Back to contents

Weedy (common)

seadragons

'Weedies' grow to about 46 cm in length.

Adults are usually reddish with yellow spots and purple-blue

bars. Small leaf-like appendages occur singularly or

in pairs along the body. A few short spines also occur

along the body. It is quite easy to determine the gender

of a weedy seadragon. A male weedy has a shallow body

width and is generally darker in colour than the female.

Weedies have been recorded from Geraldton in Western

Australia along the southern Australian coastline -

including Tasmania - to Port Stephens in New South Wales.

A male weedy seadragon. Photo by Graeme

Collins.

Back to contents

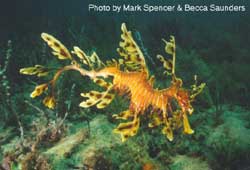

Leafy seadragons

‘Leafies’ are slightly smaller than weedies,

some growing to 43cm, however most reach an average

of 30cm. Their leafy appendages are more numerous and

branching than on weedies and look distinctly like fronds

of brown seaweed. Adults are green to yellow-brown with

thin, pale dark-edged bands. As with many species of

seahorse, seadragons are able to change colour depending

on age, diet, location or even their stress level. Unlike

weedies, the leafy seadragons' eyes are located slightly

above the snout. Leafies have several long sharp spines

along the sides of the body. These spines are thought

to be used as a defence against attacking fish. New

research has shown that leafy seadragons have a highly

sophisticated navigation system, venturing hundreds

of metres from their base but returning precisely to

the same spot (Connolly 1998). The leafy seadragon has

a much smaller range than the weedy. Leafies have been

recorded from Geraldton in Western Australia along the

southern Australian coastline to Wilsons Promontory

in Victoria.

Leafy seadragon, Fleurieu Peninsula

(South Australia). Photo by Mark Spencer & Becca

Saunders.

Back to contents

Seaweed

swayers

Seadragons resemble swaying seaweed,

which can make them difficult to find in their natural

habitats. They are slow moving and therefore rely heavily

on camouflage for their survival. Their bright colours

are revealed in sun dappled waters or under bright camera

lights. Both species of seadragon inhabit rocky reefs,

seaweed beds, seagrass meadows and structures colonised

by seaweed. In the wild they live individually or in

pairs are more often seen in shallow coastal waters.

They feed by sucking plankton, larval fishes and small

shrimp-like crustaceans, called mysids, into their small

mouths. This is done by quickly expanding a joint on

the lower part of their snout, causing a suction force

that draws the food in (Groves 1998).

Back to contents

Male mothers,

wrinkly tails and egg cups

As spring approaches, male and female

seadragons pair. The female develops around 300 orange

eggs in her lower abdominal cavity. The lower half of

the tail on the male begins to form fine blood vessels

near the surface, swells and looks wrinkled. He then

develops about 120 small pits or 'egg cups' on the tail

and the eggs are transferred from the female and fertilised.

Although this transfer has yet to be observed, we suspect

it occurs in the dark, pre-dawn hours. Dragon Searchers

in Tasmaina are using infra-red video equipment to try

and observe the egg transfer and other breeding behaviour

of weedy seadragons.

The male's tail swells and looks wrinkly

as the 'egg cups' develop before egg transfer. Photo

by Andrew Melville.

The male carries the eggs for an incubation

period of about 4 weeks. The young seadragons hatch

over several days. This staggered hatching is to aid

dispersal and avoid competition for food amongst the

young. At birth, seadragons are around 20mm long and

are often differently coloured to the adults. The young

are preyed upon by fish, crustaceans and sea anemones

and live in different places to the adult seadragons.

The young dragons are fast growing, reaching 20cm after

one year and a mature length after about two years.

It is not known how long wild seadragons live. In captivity

it is thought that they can live for about 5 to 7 years.

Seadragons, along with all other fish, have ear bones

(otoliths) that show growth rings. New growth rings

are continuously produced throughout the seadragon's

life. One of the reasons dead beach-washed wild seadragons

are very important is that it may be possible to age

the beach-washed seadragons from these growth rings,

therefore giving us a better understanding of the age

of seadragons in the wild. The general health of the

seadragon throughout its life and its changing growth

rates can also be determined from the otoliths.

Back to contents

'Take two

seahorses and go to bed'

There

is increasing concern about the future of seadragons

and other syngnathids in Australian waters. Seahorses,

seadragons, and in particular, pipefish, are threatened

globally by habitat destruction. An estimated 20 million

seahorses (but not seadragons) are taken each year for

traditional Asian medicines. The international trade

in seahorses and pipefish involves more than 20 countries

and is growing. There

is increasing concern about the future of seadragons

and other syngnathids in Australian waters. Seahorses,

seadragons, and in particular, pipefish, are threatened

globally by habitat destruction. An estimated 20 million

seahorses (but not seadragons) are taken each year for

traditional Asian medicines. The international trade

in seahorses and pipefish involves more than 20 countries

and is growing.

Fortunately seadragons currently are

not used for the medicine trade, however they may be

targeted in the aquarium fish trade. Keeping live seadragons

is extremely difficult and collectors often target males

with eggs, hatching out and selling the young. Removing

these brooding animals from the wild populations may

impact on local populations of seadragons. To date,

no successful, closed cycle, captive-breeding program

has occurred (ie getting a generation of captive-raised

seadragons to breed). Economically and environmentally,

it makes sense to limit collection and export of this

species until we know more about them. Seadragons have

a specific level of protection under fisheries legislation

federally and in most Australian states where they occur,

such that it is illegal to take or export them without

a permit.

Back to contents

Why survey

for seadragons?

It is only recently that the threats

to marine biodiversity have been recognised. These threats

relate indirectly or directly to development of coastal

areas and pollution or exploitation by humans. There

are numerous examples of marine mammals and birds that

have become extinct or are threatened but little is

known about the vast majority of marine invertebrates

and fish (Jones and Kaly 1995), or their status.

Many people think of fish in the ocean

as an inexhaustible resource. Most of the research on

fish in Australia is on commercial species and little

is known of the lives of even the most common non-commercial

species. Divers who know their local areas and favourite

dive spots can often see changes but are often a quiet

minority. By making divers familiar with recording observations,

the seadragon monitoring program aims to encourage divers

to be pioneering researchers, since virtually nothing

is known about many marine creatures, in the wild or

captivity.

Most people are familiar with the "charismatic

marine mega-vertebrates", marine mammals such as whales,

dolphins or sea-lions. In southern Australia marine

protected areas for threatened species relate to sea-lions

and more recently in South Australia proposals of habitat

protection for Southern Right Whales. There are however

a number of fish and invertebrate species and their

habitats that may be threatened, but there is little

information available to assess their status or define

areas for habitat protection.

There are usually limited resources for

fisheries managers to investigate the conservation and

management of fish that are not directly targeted by

'traditional' recreational or commercial fishing. With

this in mind the Marine and Coastal Community Network

(SA), the Threatened Species Network (SA) and the Marine

Life Society of South Australia undertook to develop

a database of leafy and weedy seadragon sightings. Seadragons

are potentially a "flagship species" for marine conservation

in southern waters. They are popular species that can

serve as a rallying point for major conservation initiatives

(Noss, 1990).

Fish such as the seadragon highlight

the high degree of uniqueness or endemism of species

that exists in southern temperate waters. For example,

as well as the many unique fish and invertebrates, there

are twice as many species of seaweeds alone in southern

waters than on the Great Barrier Reef and off Ningaloo

Reef in Western Australia. Australians are not generally

aware of the immense marine biodiversity they have off

their southern coast and the spectacular and unique

environments that exist there.

Water-watch, Frogwatch and Environmental

Protection Authority programs use frogs as a "charismatic"

and useful indicator of freshwater water quality monitoring.

Seadragons are colourful marine fish that could be adopted

in a similar "mascot" capacity for marine water quality

awareness. It has been suggested that seadragons may

be sensitive to changes in water quality. Long-term

monitoring of seadragon populations could also be useful

as indicators of changes in water quality, especially

in relation to catchment events.

There is widespread interest in developing

community processes for the monitoring of salt-water

environments, including mangroves, estuaries and sea

grass. The Marine and Coastal Community Network hopes

to encourage a adoption of similar community initiatives.

Awareness generated by the Dragon Search project has

been beneficial in generating interest in other marine

monitoring projects such as Reefwatch, a community reef

monitoring program.

A basic principle of the project is the

assumption that learning about the marine environment

and sharing your knowledge and enthusiasm is the one

of the best ways to help make a difference. Seadragons

are animals which stir up emotion and have encouraged

a lot of curiosity in divers, beachcombers, teachers

and students. By reducing marine pollution and conserving

the marine environment for species such as seadragons

we can also ensure a healthy environment for all our

marine life.

Increased awareness and involvement of

local communities may help prevent poaching of seadragons

and encourage protection of both the species and its

habitat. Responses to the project have already reflected

this, with people from around the country contacting

the project coordinators to express concern over potential

threats. The ultimate aim of the project is to provide

information to identify sites suitable for Marine Protected

Areas for the species and habitat and to create an atmosphere

of responsibility and ownership in the community towards

these areas.

Back to contents

You could

be a pioneering scientist

Some of the life history of seadragons

is known from observing captive and, to a lesser extent,

wild animals. More information about the basic ecology,

distribution and movement in the wild needs to be collected

to enable sensible management of these species. You

can be a pioneering scientist by participating in Dragon

Search.

Back to contents

How to

get involved!

Many recreational divers already record

sightings of seadragons in their dive logs, and many

other people observe beach-washed marine flora and fauna.

It is a simple and most helpful step to transfer relevant

information on seadragons to the Dragon

Search sighting sheets. It is also extremely beneficial

to have regular checks of the same sites and hence obtain

information on trends in seadragon abundance over time.

Even if you don't see seadragons on your dive, that

information can be useful, especially if you have seen

them at the site before. Remember safety comes first.

Organise your underwater surveys as you would any other

dive.

Dragon Search Seadragon Sighting Form

that is used to report seadragon sightings.

Back to contents

What are we

doing

Dragon Search no longer has part time

coordinators in each Australian State where seadragons

are known to occur. However, the data submitted will

be pooled and can be periodically assessed to expand

the existing reports.

In South Australia, the Reef Watch Feral or In Peril

program continues to provide education about seadragons.

Back to contents

What are the

principal aims of Dragon Search?

1. To increase awareness, understanding

and appreciation of syngnathid fish and the need for

their protection and conservation.

2. To actively promote habitat protection

and species conservation through the abatement of threats

affecting the marine environment and syngnathid fish.

3. To establish a pilot program of community-based

monitoring and a database that can be used as an aid

to increase knowledge and define key habitat areas for

syngnathids.

4. To instil community pride and custodianships

for our unique marine environment and wildlife.

Back to contents

That face looks

familiar

A research team from Griffith University

has been using photographs to identify the facial patterns

of individual Leafy Seadragons and sonic tagging techniques

to learn more about their ecology and territorial behaviour.

If you would like to contribute, the photographs need

to be high quality, and show well-lit, close-ups of

the face. You may like to photograph or video seadragons

at the sites you dive regularly, to try and identify

individuals. Observations of activity at night are also

valuable.

Individual leafy seadragons can be identified

by their distinctive facial markings. Photo by Andrew

Melville.

Back to contents

The database

Information from the sighting sheets

is automatically stored in a database. Our database

containing the raw data is confidential and NO site

specific information is passed on. Analysis of the Dragon

Search databases from each State will be released as

they are produced. These reports will based on Australia's

marine bioregions. Dragon Search has actively encouraged

syngnathid protection legislation nationally and at

a state level. With the on-going success of this community-based

survey program we hope to encourage the development

of databases for other endemic and protected fish and

invertebrate species.

Dragon Search promotes the need for marine

reserves, not just for seadragons, but to conserve a

comprehensive and representative range of our unique

marine life and habitats. No-take marine reserves provide

refuges for fish and therefore provide benefits to the

local marine environment and in the long term the fishing

industry. Dragon Search also supports the principles

of Ecologically Sustainable Development.

Back to contents

I don't

dive or snorkel, but want to help...

Seadragons can be found on the beach

because they have bony-plates which help preserve their

bodies after death. Beachcombers' reports of beach-washed

seadragons can give us valuable information from areas

that may be unsuitable for diving, following storms

or in the colder months when diving activities generally

decrease. Historical records and fishermen's and field

naturalists’ observations are also useful.

Back to contents

References

Connolly, R. (1998).

Measuring the home range of leafy seadragons. The

Dragon's Lair Vol. 3 No. 2 : p3.

Gomon, M.F., Glover,

J.C.M. & Kuiter, R.H. (eds.) (1994). 'The Fishes

of Australia's South Coast'. (State Print : Adelaide).

Groves, P. (1998).

Leafy seadragons. Scientific American December

1998 : 54-59.

Jones, G.P. &

Kaly, U.L. (1995). Conservation of rare, threatened

and endemic marine species in Australia, State of

the Marine Environment Report, Technical Annex:1,

The Marine Environment, Ocean Rescue, DEST, pp 183-191.

Noss, R.F. (1990).

Indicators for measuring biodiversity: hierarchical

approach. Conservation Biology 4 : 355-364.

Back to contents

© Copyright Dragon Search 2000

TOP

|